A young boy missing the visual centre of his brain retains vision – stunning researchers.

In a first-time discovery (shocking doctors and researchers alike) a young Australian boy has retained his vision despite missing the visual cortex of his brain. Due to a rare metabolic disorder, the seven year old boy – referred to as ‘BI’ – showed no flaws in his vision other than that of nearsightedness. Following the initial discovery and an MRI scan, the Bourne Group at ARMI found an area of the boy’s brain compensating for the lack of vision, leading to the hypothesis that the brain had adapted to the lack of visual cortex. This discovery and subsequent research was published recently in “Neuropsychologia”.

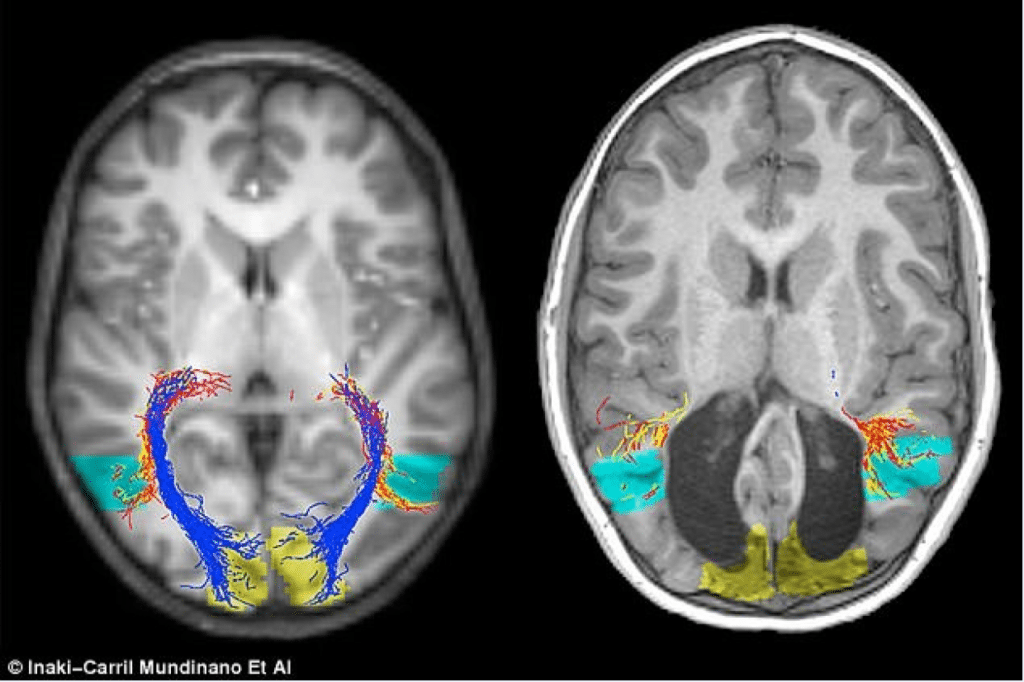

“It has been amazing to confirm in a human patient our previous animal research studies” stated Dr Iñaki Carril Mundiñano, from the Bourne Group at ARMI. “The reorganisation of the visual pathways we detected in patient BI is similar to what James Bourne’s lab described in Current Biology in 2015”.

Until now, those with damage to the visual cortex are said to have ‘cortical blindness’ due to disruption in the processing of electrical signals from the eye. Some patients with similar lesions that occurred later in life have the ability to respond to visual stimuli without consciously ‘seeing’, this is known as ‘blindsight’. However, BI is entirely conscious of what he sees. In a series of tests at Monash University, BI was able to identify colours, name objects, discriminate between faces and identify their emotions. This miraculous discovery is a first in the field, where someone missing the entire visual cortex displays near-normal vision.

Researchers from the Bourne Group have put forth the idea of a ‘flexible brain’ suggesting that at a young age, the brain is able to adapt and overcome certain issues. Compared to other children his age, BI’s MRI scan showed more neural fibres running between two areas of the back of the brain near the visual cortex. These two areas refer to the pulvinar and middle temporal area. As a part of the thalamus, the pulvinar is involved in relaying sensory signals. The middle temporal area helps detect motion. These adaptations shown in BI have been seen in previous studies in monkeys, who were observed to preserve the same connections between the pulvinar and the middle temporal area. The fact that this kind of plasticity is present in humans is perhaps a predictable yet still very staggering discovery.

These findings suggest that young brains can adapt to losses and learn to reroute the processing of visual information to other brain systems, compensating where needed. A huge benefit for children like BI who otherwise would have faced a life of visual impairment. Today, BI enjoys his remarkable vision; playing video games and soccer with his friends. The discovery has left the Bourne Group with more questions than answers ushering in a new year of focused research and studies into this exciting new area.

“This [provides] a big [source of] motivation to keep studying the function of the pulvinar nucleus, that is one of the key brain structures in BI’s visual abilities. We would also like to carry out some functional MRI studies with BI; there are so many aspects of his visual brain that we still don’t understand” commented Iñaki. “This study has been an international collaboration with Dr Melvin Goodale from The Brain and Mind Institute (The University of Western Ontario) in Canada and with Dr Marc Sarossy from the Centre for Eye Research Australia in Melbourne.”

The original research paper is available online here

For more information on Dr Iñaki Carril and the Bourne Group at ARMI, please visit their page.

Contact Information

Dr Iñaki Carril

Research Fellow

Phone: +61 (03) 9902 9623

Email: inaki.carril@monash.edu

Notes to Editors About ARMI

The Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute (ARMI) is dedicated to unlocking the regenerative capabilities of the human body. ARMI is a medical research centre based at the Clayton Campus of Monash University. Boasting 17 research groups studying a variety of regenerative approaches, ARMI is one of the largest regenerative medicine and stem cell research hubs in the world.